In 2012, I left my job as COO of the Naxos group and started Proper Discord Ltd to help people to run their own labels. My first client was the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, and we launched a label in October 2012. Four years later, King’s College is the UK’s best-selling new classical label*. I’ve delivered a balanced budget and trained an existing part-time employee to take on a new full-time role, running the college’s recording activities. As of this week, my job is done. I’ve worked on a lot of label launches over the past few years, but this has been the most interesting. Here are some things I learned:

1. You have to know why you’re doing it.

I’ve written this before, but it bears repeating that, unless you know why you are doing something, you will never be able to clearly determine if it was successful. It is easy for a room full of people to each have a different idea of what a project is and what it is for. A strategic planning document will help with this, but you cant measure every single decision against a strategic planning document. You need a guiding principle. Mine was “make us look good and don’t lose too much money” and became “keep up the good work but find a way for this to pay for itself”. An instruction short enough to tweet is an instruction short enough to remember.

2. “Label” doesn’t mean what it used to.

Against a background of declining sales and waning investment from EMI, the choir (and college) needed to understand how recordings fitted into their life. Once upon a time, that meant LPs and a bit of sync licensing. Today, it means promotional films, viral content, social media posts, free streams, free downloads, paid streams, paid downloads, CDs, SACDs, DVDs, Bluray, sync, terrestrial TV, digital TV, and everything in between. For King’s College, the plan involved a mixture of mass-market and premium products for the traditional SACD/CD/Download/Streaming market, as well as webcasts, free streaming and the occasional free download. The choir, which previously didn’t even have a Facebook account, now has a significant social media presence and a Youtube channel, makes weekly webcasts, records every chapel service, releases four albums a year and uses self-produced digital content in almost all its marketing activities. We even convinced the Chaplain to participate in a musical April Fool. All this required teamwork, much of which was coordinated with Intermusica, the choir’s agency, who were also instrumental in making sure recording and touring plans dovetailed neatly. The recordings plan originated with Intermusica before I started work on it, and its continued success owes much to their enthusiastic and imaginative input.

3. Be careful what you call it.

You want your name to be descriptive without being limiting. LSO Live is really clear branding, but what if they want to release a studio recording? Sometimes you need to create a new separate entity, like Berlin Phil Media, SFS Media or CSO Resound.

If you’re only making CDs it might make some sense to name your “label” something entirely new, like the Sixteen’s label, CORO, which has become a big brand in its own right. This was certainly the right move in 2001, when CORO started.

If the goal was to promote their choir, why did New College call their label Novum? If there’s no real prospect of a messy divorce (like Grange Park Opera’s departure from The Grange) then why have a name at all? In our case, recordings were to become integral to the choir’s core activities, and this was supposed to make the college look good, so we decided the college would be the brand.

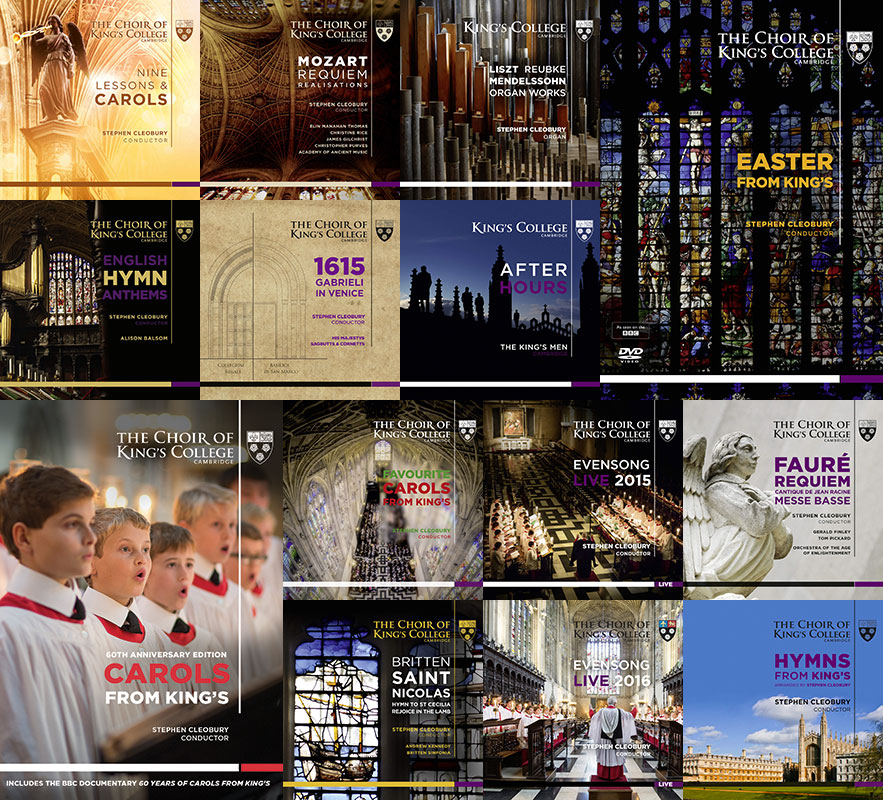

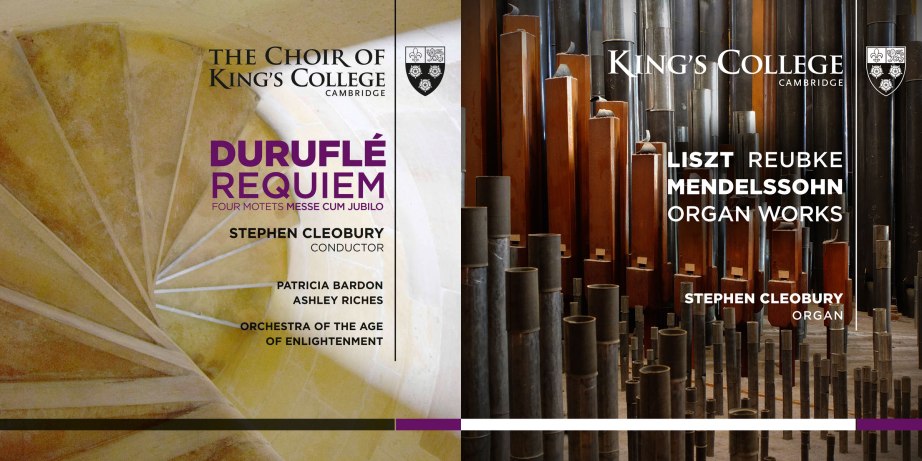

We had to be careful with our branding. When your own-label artist’s name is so long it has a comma in it, you don’t want to print it twice on the cover. It’s almost OK that the LSO gets name-checked five times on the cover of this album. LSO is short. With plans involving other orchestras and lots of soloists, we decided to put the name of the choir on there once, make it big, and central to our branding.

We already has a logo for the college:

So we made one for the choir:

Most records use the new logo. If the choir isn’t on the album, we use the old one in exactly the same place.

This gave us room to expand in two directions: non-CD products from the choir, and non-choir products from the college. It even allows us to record solo projects with notable alumni. The only things it rules out are things we’d never want to do anyway.

4. A brand is more than just a name or a logo

From the outset we realised we would need consistent visual messaging. Looking back over the choir’s considerable recorded legacy, I noticed almost all the choir’s old albums used the same view of the college, taken from the backs:

We used this angle just once, to match an existing book. All the others reflect the fact that the choir can go inside the chapel any time it wants, and doesn’t have to pap the college from the other side of the river.

In an effort to avoid rapidly ageing artwork, we decided to only depict the men and boys of the choir on time-specific albums. For everything else, timelessness was the goal. I worked with Grace Hsiu (a friend and former Apple colleague) on the design for the logo and cover art. Grace did a great job of developing a template we could use in future, maintaining a consistent brand without having anything like her design skills. Grace designed the first two covers. I did the rest myself.

5. If you can make better records, make better records

Every album needs a reason to exist. If that reason is “because we wanted to make it” or “because the existing perfectly good recordings of this all belong to somebody else” then that’s fine for you, but they are not reasons for somebody to buy it.

Every time we recorded something, we set out to make the best recording of that repertoire anybody had ever made, and we set out to do it in a way we could readily explain.

Our Mozart Requiem includes the largest collection of alternative realisations available in a single package. Our Fauré Requiem is the first recording of a new reconstruction of the first liturgical performance. I tracked down surviving choristers from the premiere of Britten’s Saint Nicolas to ensure our seating arrangements were authentic.

We commissioned program notes from leading academics, and had them translated by the college’s senior professors of French and German. One of our records had an optional 28-note trumpet solo. We got Alison Balsom to play it. If we could think of a way to make a record better, we did it**.

If your efforts to make better products are starting to seem a little absurd, it’s likely you’re getting a reputation for it.

6. It is hard to start as the little guy.

Conventional physical distribution is the wrong answer for almost everyone starting a label today. Between major retailers and international distribution, you could see as much as 70% of the purchase price of your product paid to other people, and this through a pipeline that takes a lot of work to set up and maintain. For this to be ok, you have to be selling way more CDs than you could possibly shift on your own.

King’s College sells a lot of CDs through its own shop, but it also has a large international diaspora of older fans who expect CDs, not digital products, so we had to find a solution.

Distribution for new labels is hard because there are lots of deals to set up, and you’re n a weak bargaining position. Instead of jumping through these hoops, we stepped around them and partnered with an existing label (LSO Live). The increased volume improves their bargaining power over time, we got to sign one contract instead of fifty, and we were able to start at the top end of the market. This doesn’t just help with the big things, like a good deal on physical distribution in the US. It also means you don’t have to do direct deals with specialists like the excellent Hyperion store.

7. You are your own worst competitor.

Unsurprisingly, the best-selling titles in the King’s College catalogue are the Christmas titles. These are products which, essentially, already exist on other labels. Orchestras often have this problem, but King’s College has it to a unique extent. Getting retailers to support the new recordings over old ones was always going to be a struggle, and it takes every trick in the book to make it work. A well-established distributor is great for this sort of thing.

It gets easier over time, because the new stuff crowds out the old stuff. It’s a challenge for a busy ensemble to build a catalogue quickly, but using live and archival recordings alongside new studio sessions gave us a chance to reach critical mass. Your strategy towards competitors may differ across different platforms and modes of consumption, so it may make sense to release (or promote) different subsets of catalogue on streaming and download platforms.

8. It takes two years to make a record and five years to build a label.

Smaller ensembles can be a little more spontaneous, but to really prepare for a recording and then finish it beautifully in time to promote it far ahead of launch, you need to plan two years in advance and allow twelve months between the recording date and release date. It is possible to do it faster. I’ve got it down to twenty minutes on some projects, but successfully releasing an old-school physical product takes time. At King’s College we released two albums in our first year, but this quickly increased to four a year. To start with it is very hard to project income for a new recording enterprise, but as the catalogue grows you get more signal and less noise. For the last three years we ended up with less than 5% variance from the projected P&L. A different label with a radically different business model might turn a profit on a shorter timescale, but five years is a sensible period in which to expect a successful label to become profitable. The copyright term on a sound recording is now 70 years, so there’s plenty of time to exploit them.

9. Being good to work with is worth about 25% of your operating budget.

Goodwill is difficult to quantify, but few would argue that you save money when people want to work with you. Labels rely on a variety of professional service providers, many of whom have the scope to deliver considerably more than is strictly required by any contract that might exist. You can make whole products out of this extra work, and then sell them for money. Some of the best PR we got for the label came as a result of partnering with Dolby to release our Gabrieli album in their new Atmos surround format. They gave us incredible support with the recording and post-production and even hosted a launch event, all free of charge. Over four and a half years, between reduced fees, extra work, free promotion and advice, I estimate the free services we got amounted to 25% of our operating budget. For most labels, that’s the difference between a profit and a loss, and it isn’t a zero-sum game: a lot of the things people gave us cost them nothing, but would have been expensive for us to buy elsewhere. Manners cost nothing, but politeness certainly isn’t worthless.

10. There are many measures of success.

If your goal is “make money” then you can check your bank balance. If your aims are more complex, you’ll need a more complex way to measure it. A question like “is this making us look good?” requires more sophisticated measurement and nuanced understanding than “do we have more cash” but it’s still possible.

In its first year as a label, King’s College got more press coverage for its recordings than for all its research and other academic activity. It’s a surrogate variable, but it’s an indicator of success, and you can measure it with something as simple as Google Alerts.

Recorded media projects have attracted significant philanthropic support. If somebody gives you £100,000 to keep recording things, you look pretty good to them.

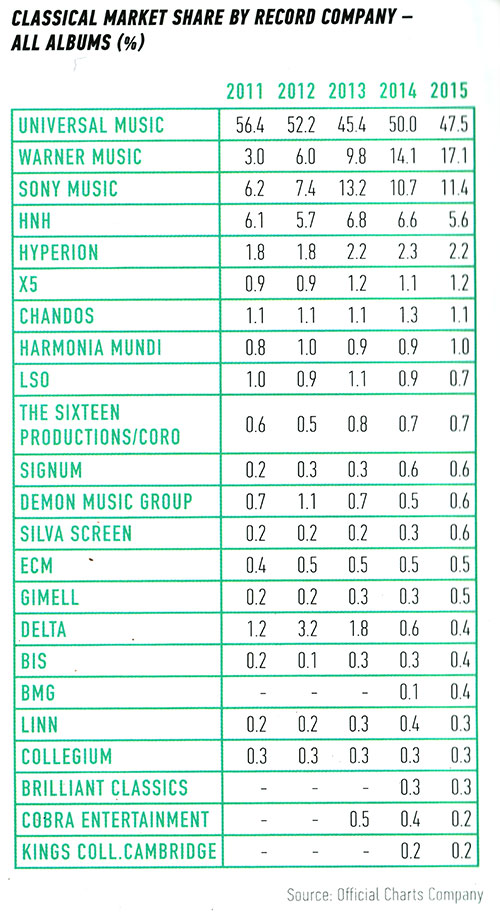

Charts tell you how you’re doing relative to everybody else. There have been several occasions over the last four years when King’s College has had more albums in the top ten than Warner or Decca, the two major labels holding the bulk of the choir’s back-catalgoue.

With Nine Lessons & Carols, we had an unusual opportunity to compare our first product to an almost identical album released by EMI some years earlier. Although the recorded music market had contracted by 50% in the intervening years, we still sold twice as many copies worldwide. This is a fairly good sign our marketing worked.

If recordings were improving the choir’s reputation, you’d expect it to get better gigs – and that’s exactly what happened, with increased fees, debut performances at prestigious venues and its first ever prom, performing repertoire from one of our most successful albums (Fauré’s Requiem). It’s not often you can draw an unambiguous line from a profitable recording project to a sold-out televised gig at the Albert Hall, but by the time it happens, you’ve already won the argument.

If you’d like to discuss your label, recording strategy or other new media projects, contact me at mail@andydoe.com or check out my work at www.andydoe.com.

* I’m basing this “best-selling new classical label” claim on the BPI’s Music Market 2016 report, which includes a table of classical labels by market share, itself based on Official Charts Company data.

It doesn’t tell you how many records any of the other labels sold, but it does list every label that sold more classical records than we did. They’re all considerably older and have considerably larger catalogues. King’s College sells 20x as many copies per title as the industry average. I’m happy with that.

** “We” here means Stephen Cleobury (the most complete musician I have ever met), the choir (the most professional group of musicians you could hope to encounter, half of whom are younger than the iTunes store), numerous fellows of the college and the staff of the choir office, chapel office, computer office and college accounts department (who all said “yes” to things when they could easily have refused, and put in extra work to absorb recording as a new part of daily life at the college), Benjamin Sheen (who as Recordings and Media Officer rebuilt the college recording system and then produced and engineered about half the catalog on it), the team from Abbey Road (Simon Kiln, Arne Akselberg and Richard Hale, who taught me more about sound recording in a week of sessions than I learned in years at college), the team at LSO Live (who bent over backwards to make extraordinary things happen at short notice) and Kate Caro and her team at Intermusica (who came up with the idea to do this in the first place and supported the project every step of the way). Some of these people are credited in the CDs, but many are not. I am extremely grateful to them all.